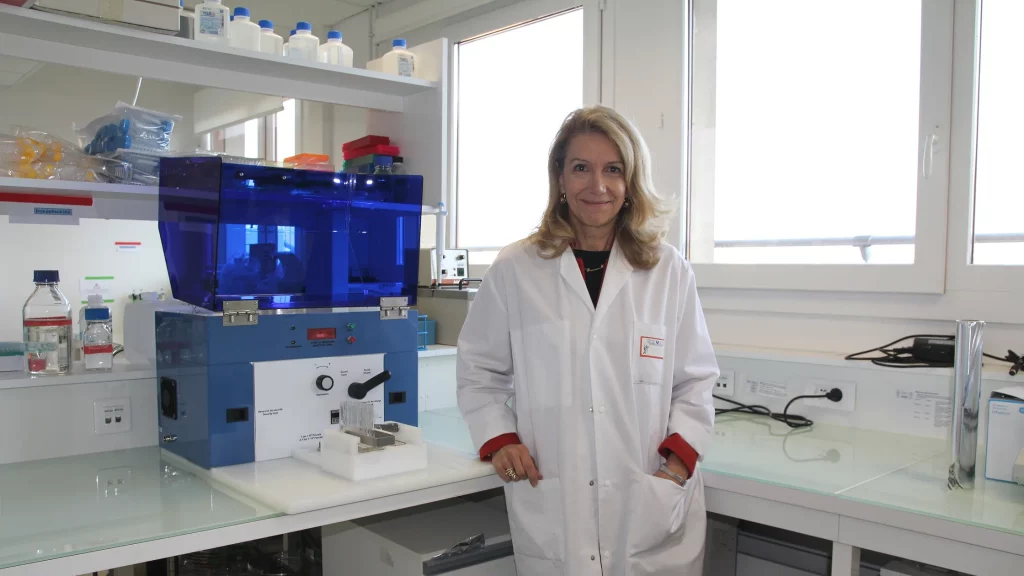

Oncologist Patrizia Paterlini: «I look for tumor cells before the tumor becomes visible, which is why I patented a test that looks for tumor cells in the blood in the very early stages of development»

“I chose research because, as an oncologist, I saw too many patients die—I felt powerless,” says the researcher who patented a method to search for cancer cells in the blood at the very earliest stages of the disease.

By Veronica Bianchini (translated from Italian: https://www.vanityfair.it/article/loncologa-patrizia-paterlini-brechot-cerco-le-cellule-tumorali-prima-che-siano-visibili-per-questo-ho-brevettato-un-test-che-le-cerca-nel-sangue-nelle-primissime-fasi-di-sviluppo)

June 24, 2025

“I chose research because, as an oncologist, I saw too many patients die—I felt powerless.” Patrizia Paterlini’s voice is steady, the voice of someone who has learned to persevere. This is how the story begins, almost as a natural choice, of one of Italy’s most important scientists: a woman who, in medicine, has sought not only answers, but answers that arrive as soon as possible. Because time, when it comes to cancer, is crucial. That “before” became her life’s mission: intercepting circulating tumor cells in the blood before the tumor is visible. Before it’s too late.

To do this, she developed a method that she patented. And she is one of the very few women to have done so. In 2024, 25% of patent applications submitted to the EPO (European Patent Office) from European countries included at least one woman among the inventors. This figure drops to 21% in Italy. Among the main countries submitting patents, Spain has 42% of applications with women inventors, France 32%, and Belgium 31%.

Doctor, how did you come to research?

“I chose medicine because it seemed like the most fascinating field: a mix of science and humanity, something that truly concerns people. I had a classical education in Italy. Medicine was the field that interested me most, and then I gravitated toward oncology. There, I was struck by the fact that oncology is a science that hasn’t solved the problem: patients still die and I couldn’t do anything to prevent it. This affected me very personally: I saw many patients die and experienced my own powerlessness firsthand. That’s when I felt the need to move into research. It’s a job that absorbs more than 100% of your life. But if you love it, you can’t do without it.”

And how did it go?

“I realized that searching in the blood for tumor markers to identify when a tumor becomes invasive at an early stage is extremely important. So I specialized in the field of liquid biopsy: this means using blood—or other biological fluids—to detect, monitor, and treat tumors. In particular, I work on circulating tumor cells: these are cells that detach from the tumor and enter the bloodstream. This can happen very early on. They are extremely rare and hard to detect. If we can intercept them early, before they settle in other organs and cause metastases, we can prevent the spread of cancer. These circulating tumor cells are the killer. Identifying them early means stopping metastases from forming.”

At first, then, you were studying these cells to prevent metastases, not because you had realized these same cells could reveal the presence of cancer early on.

“Yes, because knowledge in medicine evolves very quickly. Around the 2000s, it became clear that even when a tumor was invisible, it was releasing tumor cells. The problem to solve was how to isolate and study them. At the time, it was thought impossible to isolate these cells from the blood. In 10 milliliters you have billions of red blood cells, millions of white blood cells… and maybe one or two tumor cells. Not only that: they are also very different from each other. You can’t recognize them with just one marker. Everyone told me it couldn’t be done. But I saw no alternative. So I persisted.”

Until ISET, the method you patented. How does it work?

“It’s a method that isolates the larger cells—the tumor cells—by removing the smaller ones, which are the blood cells. Once isolated, these cells remain intact. So we can then analyze them with a wide range of techniques. And the most important thing is the sensitivity: if we put a single tumor cell in a blood sample, we can recover it more than 95% of the time. Our method is the most sensitive and the most specific. We patented the device and the process.”

So today, if I took this test, could you tell me if I have tumor cells even without a visible tumor?

“Yes. And this is a crucial point. Tumor cells can already be in the blood even when the tumor is still invisible to diagnostic tools. However, we can’t always tell where they come from. Organ-specific tests, with precise markers, would be needed, and these are not yet widely available.”

But what happens if you find these cells, but don’t know where they’re coming from?

“That’s a fundamental question. It’s one thing if you’ve already had a tumor and we’re looking for specific cells, maybe from breast cancer. It’s another if we use it as a general prevention tool. We’re in the realm of innovation: we don’t have all the answers yet, but we can start building them. In the very early phase, when the cells detach from a tiny tumor mass, medical knowledge suggests the body can eliminate tumor cells if the immune system is strengthened. A healthy lifestyle and treatments to boost the immune system could be useful before a real tumor develops. This opens up incredible possibilities for prevention.”

So the future goal is to use it as a screening tool?

“Yes, but it will take time to get there. Medicine works based on guidelines. A screening test must be defined, tested in vitro, then validated on a population at risk, and finally approved by regulatory agencies. It requires significant funding, years of work, and studies on thousands of patients before it reaches the public. No multi-cancer test has yet been officially approved. It’s hard to find funding, so we decided to first develop tests that detect a specific type of cancer.”

But doesn’t the patent slow things down?

“Companies that invest money would have no incentive to fund research, because many others could use the invention.”

What have been the hardest moments in this journey?

“There have been many. Sleepless nights, rejections, the sense of powerlessness. Obstacles. The death of a very young collaborator who developed colon cancer. I thought about giving up. But then I remember why I do this: for those patients I saw pass away without being able to help them. When you realize that a discovery can truly change someone’s fate, you can’t stop. Not even when everything tells you to. For me, success will be when these efforts reach patients and early diagnoses can be made, eliminating cancer. My dream is for these tests to become routine and accessible to everyone at low cost.”